For years I’ve heard about payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) as a promising strategy for cities to raise funds from tax-exempt organizations. What I didn’t know is that PILOTs recoup a tiny fraction of the would-be tax burden.

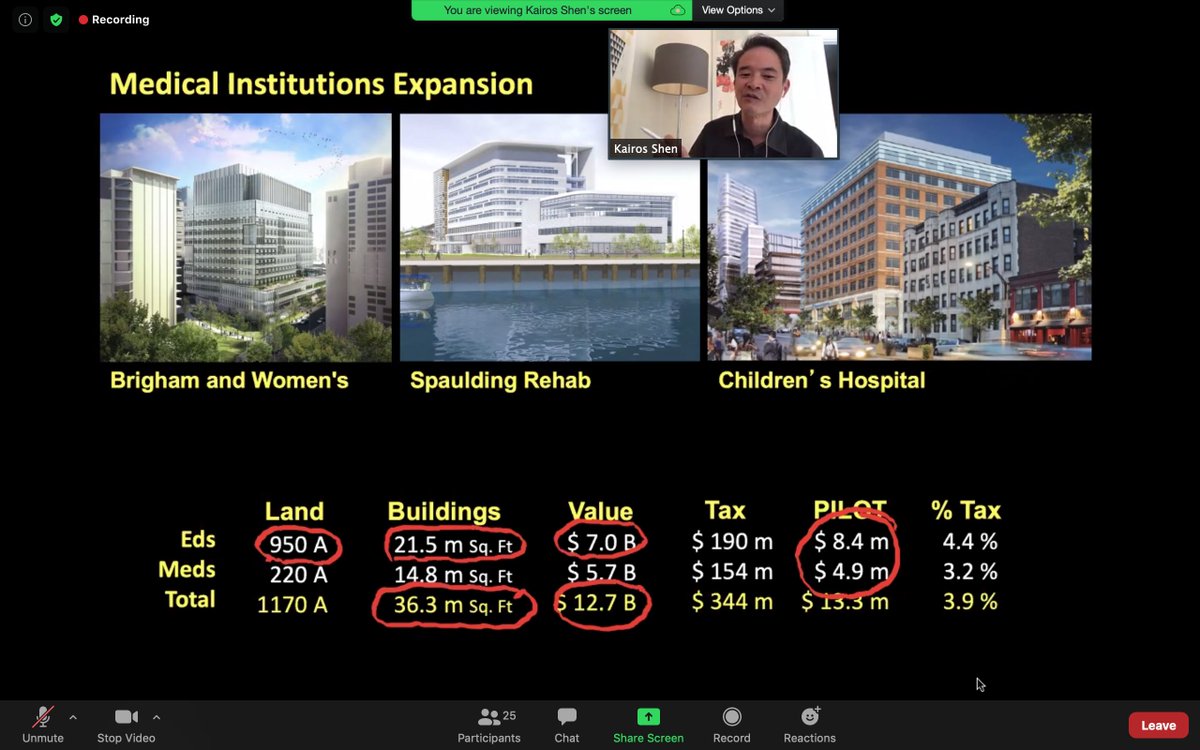

In Boston, PILOTs collect less than 5% of what taxes would. The following screenshot is from a class I took at MIT in Fall 2020 with Kairos Shen, who served as the City of Boston’s Director of Planning for thirteen years. The table at the bottom focuses on two of the largest tax-exempt sectors in the city, estimating the land value, the would-be tax burden, and the PILOTs the city collects from each sector annually. Though institutions like Emerson College and Boston University contribute $8.4 million to the city’s coffers through PILOTs, they’re paying just 4.4 percent of what their property taxes would be. And though Brigham and Women’s and the Children’s Hospital contribute $4.9 million in PILOTs, they’re paying just 3.2 percent of their property taxes.

Boston is a high-water mark for PILOTs: according to the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, Boston collects far more money from PILOTs than any other US city.

Universities, hospitals, & other tax-exempt organizations are tax-exempt for a reason: they provide many spillover benefits to the public. But amidst COVID-induced budget shortfalls & powerful calls for new social investments, it’s worth considering whether they should pay more.

To channel my former Brookings colleague Vanessa Williamson, you know what’s better than PILOTs? Paying taxes.

Originally tweeted by Nathan Arnosti (@n_arnosti) on October 14, 2020.